You have the talent in large organizations. You have the resources in large organizations. So why can’t they be more innovative?

—Sam Palmisano, Former CEO, IBM

How long do you expect to live? Most Americans can plan on reaching the age of seventy-nine, Japanese almost eighty-three, Liberians only forty-six. Now, how long will your company live? It turns out that it’s a lot less than you are to make it to a ripe old age. Research has shown that only a tiny fraction of firms founded in the United States will make it to age forty, probably less than 0.1 percent.1 Of firms founded in 1976, only 10 percent survived ten years later. While this is somewhat understandable because of the high mortality rate of newly founded firms, other research has estimated that even large, well-established U.S. companies (maybe like the one you work for) can expect to live only between another six to fifteen years on average.2 Underscoring the fragility of organizational life, McKinsey colleagues Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan followed the performance of 1,000 large firms across four decades. Only 160 of 1,008 survived from 1962 to 1998.3 They found that in 1935, the average company could expect to spend ninety years in the S&P 500. By 2005, this average had fallen to a mere fifteen years—and it continues to fall. On average, an S&P 500 company is now being replaced about once every two weeks—and this rate is accelerating.4 One-third of the firms in the Fortune 500 in 1970 no longer existed in 1983. This led one researcher to observe that “despite their size, their vast financial and human resources, average large firms do not ‘live’ as long as ordinary Americans.”5

Why should this be? We understand why our human life is limited. Studies have shown that over time, our body’s cells lose their ability to accurately regenerate themselves. Cell senescence is at the root of many of the diseases that limit our life span. But there is no obvious equivalent cause of death for organizations. When we humans are successful, we may eat too much, work too hard, exercise too little, and do a variety of things that are not good for our health. But even the healthiest among us will succumb to cell senescence. By contrast, when companies are successful, they amass all the resources needed for their continued reign. They generate financial strength, market insight, loyal customers, brand awareness, and the ability to attract and develop human capital. Used wisely, these advantages should enable them to continue their success as markets and technology evolve. Unlike us, companies have no obvious biological limitations to their continued success. Yet even successful organizations have a disturbing tendency to perish.

Consider Netflix and Blockbuster. In 2012, Fortune magazine featured Reed Hastings, Netflix founder and CEO, as its businessperson of the year. Founded in 1999, Netflix is now the world’s largest online DVD rental service and video streaming firm, with more than 100,000 titles in its library, 60 million subscribers, and annual revenues of more than $4 billion. In 2002, the year Netflix went public, prime competitor Blockbuster had revenues of $5.5 billion, 40 million customers, and 6,000 stores. Yet only eight years later, on September 23, 2010, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy; in a supreme irony, Netflix was added to the S&P 500 shortly after, replacing Eastman Kodak, another failed corporate icon.

When Netflix went public in 2002, a Blockbuster spokesperson said that it was “serving a niche market. We don’t believe that there is enough demand for mail order—it’s not a sustainable business model.”6 In 2005, as Netflix began moving into the streaming of videos over the Internet, the chief financial officer of Blockbuster said, “We don’t think the economics [of streaming] works well right now.”7

But before these public dismissals, there was a private one. In 2000, Reed Hastings flew to Dallas to meet with the senior executives at Blockbuster. He proposed that they purchase a 49 percent stake in Netflix, which would then become the online service provider for Blockbuster.com. Blockbuster wasn’t interested. Blockbuster didn’t have to buy Netflix—though it could have—to rent videos by mail. It had all the resources needed to crush a freshman firm that had revenues of only $270,000 and was a fraction of Blockbuster’s size when it went public. But by the time Blockbuster got around to renting videos by mail in 2004, it was too late.

Why did Blockbuster fail and Netflix succeed? The difference boils down to how their leaders thought about change. Blockbuster leaders were focused on growing and running today’s business: video rentals through conveniently located stores. And they were good at this. Their strategy focused on growth in new markets, increasing penetration in existing ones, and maximizing the number of movies rented. In 2003 Blockbuster had a 45 percent market share and was three times the size of its closest competitor. In 2004, as Netflix was becoming an even bigger threat, Blockbuster revenues still increased 6 percent and senior executives talked proudly about “the experience of a Blockbuster store.” In addition to extracting revenues from their existing business, the company saw opportunities for expansion through acquisitions (e.g., Hollywood Video), methods for boosting rentals, and the creation of a DVD trade-in program. Their decision to enter into the mail order and online rental business was reactive and defensive, not proactive and transformational. In hindsight, we can see that they focused on winning a game that was soon to be irrelevant.

In contrast, leaders at Netflix didn’t think of themselves as being in the DVD rental business; rather, they identified their offering as an online movie service. In Hastings’s words, “I was obsessed with not getting trapped by DVDs the way AOL got trapped, the way Kodak did, the way Blockbuster did. . . . Every business we could think of died because they were too cautious.”8 Even though their mail-in rentals caught on first, they’ve been focused from day one on how to be a broadband delivery company. “It was why we originally named the company Netflix, not DVD-by-mail.”9 The Netflix strategy emphasizes value, convenience, and selection. To deliver on these, they have been willing to cut prices and invest aggressively in new technologies ($50 million in 2006–2007 in video on demand). More important, they have been willing to cannibalize their old business to succeed in the new.

Video streaming puts Netflix revenue from DVD rentals at risk. Yet its leaders needn’t fear because they have been aggressive in moving into streaming; today more than 66 percent of Netflix subscribers use streaming, and the company has retained customers who might have otherwise moved to Hulu, HBO, or another of their many competitors. In Hastings’s view, DVD rental by mail is just one phase of the business. His goal is to have every Internet-connected device capable of streaming Netflix videos. To accomplish this, Netflix gives away the enabling software and is now on more than two hundred devices. In making this transition, Netflix is beginning to close some of its fifty-eight regional mail order distribution centers. While subscription rates for online service are lower than for DVD rentals, Netflix is beginning to save some of the $700 million that it spends for mailing DVDs. In the process, it is still growing its customer base by close to 50 percent every year.

More recently, in order to attract and maintain customers, Netflix has moved into video production and in 2015 will spend $6 billion in producing hit shows like Arrested Development and Orange Is the New Black. In producing original programming, Netflix is not seeking short-term profits but playing a game for the long haul. In the words of chief content officer Ted Sarandos, Netflix wants “to become HBO faster than HBO can become Netflix.”10

What was it about Netflix and its leadership that helped the firm transition from DVD rentals to video streaming, while Blockbuster and its management struggled and failed? This is the puzzle that is at the heart of our book. It’s a puzzle that we have been working on with companies from around the world for the past ten years in our research and consulting.

Organizational Evolution

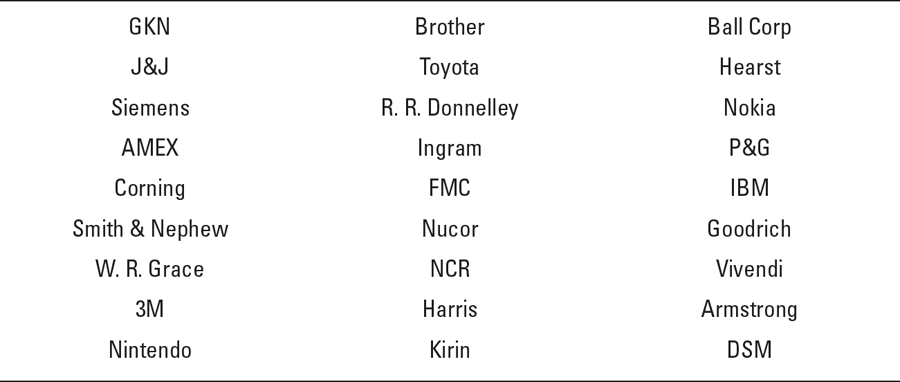

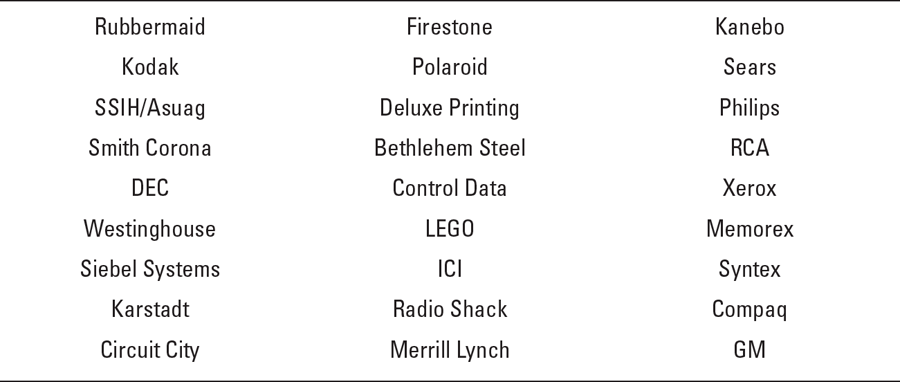

To get a sense of just how common this problem is, take a look at the companies listed in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and ask yourself: What is the difference between those in the first table when compared to those in the second?

TABLE 1.1 What Is True of All These Companies?

TABLE 1.2 What Is True of All These Companies?

Table 1.1 lists a set of companies, some large and well known, like IBM, Toyota, and Nokia, and others less well known, like GKN, DSM, and the Ball Corporation. As you scan this list, ask yourself: What do these companies have in common? It isn’t obvious since they come from around the world and represent a hodgepodge of industries. But if you think more deeply, a couple of patterns will emerge. First, these are old companies. The average company on this list is 130 years old. They’ve all been around for a long time. Only a few were founded in the twentieth century (e.g., IBM, Marriott, Toyota, 3M, and DSM). Some are genuinely old. GKN, for example, is a British aerospace company founded in 1759. Think about that for a second: How could a firm founded in 1759 be an aerospace company? The Wright brothers didn’t make their first flight until December 17, 1903.

This leads us to the second truth about these companies—and the part that is most relevant for leaders today. All of these have been able to transform themselves to compete in new businesses as markets and technologies have changed. GKN began as a coal mine and then, with the industrial revolution, became a producer of iron ore. By 1815, it was the largest producer of iron ore in Great Britain. In 1864 it began to produce fasteners (nails, screws, and bolts) and by 1902 was the world’s largest producer of these. Drawing on its expertise in metal forging, GKN began to produce auto parts and then aircraft components in 1920. In the 1990s, the company sold off its fastener business and began to provide services as an industrial outsourcer to firms like Boeing. Today it is a $9 billion corporation competing successfully in aerospace, automotive, and metallurgy and employs more than 50,000 people. These transformations and their successes have been possible only because of leaders who were able to foresee how the company could leverage its strengths as markets changed.

BF Goodrich is best known as a maker of automobile tires, but it began by making fire hose and rubber conveyor belts in 1870 and parlayed its expertise in the manufacture of rubber products into automobile and aircraft tires, and then into high-performance materials. In 1988 it sold its tire business. By 2000 it was a $6 billion aerospace firm employing 24,000 people and selling engineered products and systems to the defense and aerospace industries. In 2012, it was purchased by United Technologies. W. R. Grace is a $2.5 billion maker of specialty chemicals, but it was founded in 1854 to ship bat guano (a fertilizer) from Latin America to the United States. DSM (Dutch State Mines) was founded 112 years ago as a state-owned coal mine. Today it is a life sciences and material sciences company. When it was founded in 1913, IBM made mechanical tabulating machines. Today it is a $100 billion company that earns 85 percent of its revenue from software and services that didn’t exist even fifty years ago. Kirin, the Japanese beer company, founded in 1885, is leveraging expertise in fermentation to become a producer of biopharmaceutical and agricultural products. Hearst, the eponymous publisher, was founded in 1887, but today more than half of its revenues come from electronic media; it is a growing business while most media companies are failing.

We could expand this list to include a large number of younger companies that have also been transformed. EMC, the $14 billion maker of storage products, began selling office furniture in 1979. Today it is morphing from a maker of computer hardware into a software developer and has recently been acquired by Dell. R. R. Donnelley began 150 years ago as a printing company and today is using its core technologies to move into the fast-growing business of printed electronics (e.g., RFID tags). Amazon, famous as an online book seller, is now the largest web retailer and a major player in the provision of cloud-based utility computing. Xerox is moving aggressively from selling machines to becoming a service company. Who knows what Google will become in the next decade?

To put a finer point on what is remarkable about these companies, we must consider how they have been able to successfully transform over time. Each of these businesses was able to capitalize on its dynamic capabilities: “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments.”11 As a result, they have been able to compete in both mature businesses (where they can exploit their existing strengths) and new domains (where they have leveraged existing resources to do something new). As their core markets and technologies changed, they have been able to change and adapt rather than fail. They have built bridges to their next destinations as the footing under them was quaking. How were they able to do this?

The short answer, which we elaborate on in the rest of the book, is that they had ambidextrous leaders who were able and willing to exploit existing assets and capabilities in mature businesses and, when needed, reconfigure these to develop new strengths. We’re talking about Netflix’s ability to invest in video streaming and rent DVDs by mail; IBM’s capacity to sell large mainframe computers (the z-series server) and do strategy consulting; Cisco’s success in selling routers and switches to large corporations and developing its high-end videoconferencing product, TelePresence. This is the positive side of the story we tell.

Now, look at Table 1.2 again and ask yourself: What’s true of these firms? What is most striking is how well known many of these names are: Sears, Polaroid, Firestone, RCA, Kodak, Bethlehem Steel, Smith Corona. These are (or were) great brands. They were companies that led their industries. Yet every company on this list has either failed or had a near-death experience.

As we will see, between the 1930s and 1970, Sears was the dominant retailer in the United States and employed more than 400,000 people. Like Blockbuster in 2004, it was larger than the next three competitors combined. Today the betting on Wall Street is that within a few years, it will be gone, sold off for its real estate. Similarly, Karstadt, the great German department store chain, founded in 1881, was one of Germany’s oldest and largest retailers. By 2009 it was bankrupt while its largest competitor, Kaufhof, has prospered. In 1955, RCA was almost twice the size of IBM and was seen as having better technology. By 1986, it was gone. In the decades leading up to the 1960s, Firestone was widely seen as the best-managed U.S. tire company. By 1988 it was out of business, sold to the Japanese company Bridgestone.12 Smith Corona, founded in 1886, was the dominant U.S. typewriter company for more than fifty years. In 1980 it had a 50 percent market share. It was also one of the first firms to produce an electric typewriter and a word processor. By 2001, it was dead, its products turned into relics for collectors.13 Founded in 1857, Bethlehem Steel was once the second-largest steel producer in the United States. By 2003, it was out of business. Founded in 1937, Polaroid not only dominated the market for instant photographs but was also one of the first companies to invest in digital imaging. Yet as organizational researchers Mary Tripsas and Giovanni Gavetti show, its leadership failed abysmally to capitalize on these investments, and the company closed its doors in 2008.14

This depressing litany could go on. Kodak has been struggling for two decades; in 2012, after laying off more than 90 percent of its workforce, it declared bankruptcy. Rubbermaid, founded in 1920, was listed by Fortune Magazine in 1984 as one of America’s most admired companies. By 1999, it was failing, leading a Fortune journalist to comment, “It has to be said: This is pathetic. America’s most admired company of just a few years ago is taken over by a company most people have never hear of [Newell Corp].”15 In 2003, the Deluxe Corporation, a ninety-year-old check printing company, earned 90 percent of its revenues from printed checks. In spite of some tepid efforts to move into electronic payments, the firm chose to spin out new ventures and stick with the printing business. As electronic payments have surged, the firm has struggled, cutting costs, laying off employees, and closing manufacturing sites. Meanwhile, its spin-out company, eFunds, was bought for $1.8 billion in 2007. What’s more, the company’s main competitor, the John H. Harland Company, has moved into electronic funds transfer, data processing, and software, reinventing itself in a way that Deluxe could not.

Each of these failures is unique in its details but the same in that each represents a failure in leadership. Every company described was at one point a great success and had the resources and capabilities needed to continue to be successful. The failure was that unlike the companies in Table 1.1, the leaders of these companies were rigid in one way or another—unable or unwilling to sense new opportunities and to reconfigure the firm’s assets in ways that permitted the company to continue to survive and prosper. Instead, the managers of these firms are the corporate equivalent of Jack Kervorkian, presiding over their firms’ demise.

These examples illustrate the fundamental challenge confronting leaders today. Regardless of a company’s size, success, or tenure, we argue that their leadership needs to be asking: How can we both exploit existing assets and capabilities by getting more efficient and provide for sufficient exploration so that we are not rendered irrelevant by changes in markets and technologies? Seminal organizational scholar Jim March noted that the problem with addressing this seemingly simple question lies in the difficulty of achieving balance.16 We naturally favor exploitation with its greater certainty of short-term success.17 Exploration, however, is by its nature inefficient, risky, and maybe even downright scary. Yet without some effort toward exploration, firms, in the face of change, are likely to fail. March concluded that because of this short-term bias “established organizations will always specialize in exploitation, in becoming more efficient in using what they already know. Such organizations will become dominant in the short-run, but will gradually become obsolescent and fail.”18 We often see March’s prophecy play out in the business media.

Disruptive Innovation

But we owe the dominant explanation for why organizations fall prey to changes in technology and markets to Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen. Christensen characterizes “disruptive technologies” or “disruptive innovations” as those that create new markets through the introduction of new products or services that appeal to a new set of customers.19 Categorically, mainstream customers initially perceive these “improvements” to be less attractive than the dominant alternative. Just think back to the early days of streaming video when it was much easier to simply rent a DVD. As another example, consider the introduction of free open source software like Linux. As we will discuss later, software vendors like Microsoft and Sun Microsystems and corporate customers saw these open source offerings as inferior. And compared to the refined offerings of the dominant competitors, Linux was inferior, appealing only to technically sophisticated hobbyists. However, as Christensen observed, if these technologies improve fast enough and become good enough, they can become attractive to mainstream customers. When this happens, the result is collapsing prices and huge disruptions among the established players. Industries as varied as steel (mini-mills), retailing (online sales), pharmaceuticals (biologics), publishing (online news and books), education (MOOCs), computer hardware and software (cloud computing), photography (digital cameras and photo sharing), and entertainment (music and TV streaming) have seen trajectories that can be matched up to Christensen’s view. He says that when confronted with these seemingly minor threats, “rational managers rarely build a cogent case for entering small, poorly defined, low-end markets that offer only lower profitability.”20

Since the publication of Christensen’s book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, in 1997, there has been a substantial amount of research and writing about the importance and impact of disruption. Agreement is now widespread that organizations faced with disruption need to somehow compete in mature businesses where continual improvement and cost reduction are often the keys to success (exploitation) and pursue new technologies and business models that require experimentation and innovation (exploration). What remains unsettled is how firms can and should do this. Christensen argues, “When confronted with a disruptive change, organizations cannot simultaneously explore and exploit but must spin out the exploratory subunit.”21 For example, soon after his book was published, the leaders of Hewlett-Packard’s Scanner Division followed this advice and spun out their portable scanner unit from the legacy flatbed organization. However, the new business could not leverage the assets and capabilities of the mature business, and corporate executives were unable to give this exploratory unit the protection and oversight it needed. Once the larger company came under cost and margin pressure, the exploratory unit struggled and was subsequently closed down. This is just one example drawn from a pattern that we see based on the ripple effect of Christensen’s wildly popular advice.

In contrast, our research and consulting experience suggest that a strong separation between the past and the future can undermine the success of the new unit, too often leaving it dead in the water. As we will show, if there are assets to be leveraged in the incumbent organization (as is often the case), the exploratory organization must have access to these. Sure, it makes strategic sense to separate out the past and the future. But what is needed is a more sophisticated separation that also includes targeted integration, strong senior management support for the new business, and an overarching organizational identity. A seemingly unrelated example that illustrates this beautifully can be seen in our educational systems: one reason that many charter schools have not been successful is their lack of strategic and tactical integration within incumbent school districts.

But how can a manager decide when separation is needed, how much, and how to take advantage of existing resources? In other words, if not in the way that Christensen describes, then how can firms solve his now-classic innovator’s dilemma? We have an answer, and we’ll share it over the course of this book. To start, let us take the larger notion of disruptive innovation and recast it in terms of innovation streams that can help managers map their challenges and decide how and when to create exploratory units.

Innovation Streams

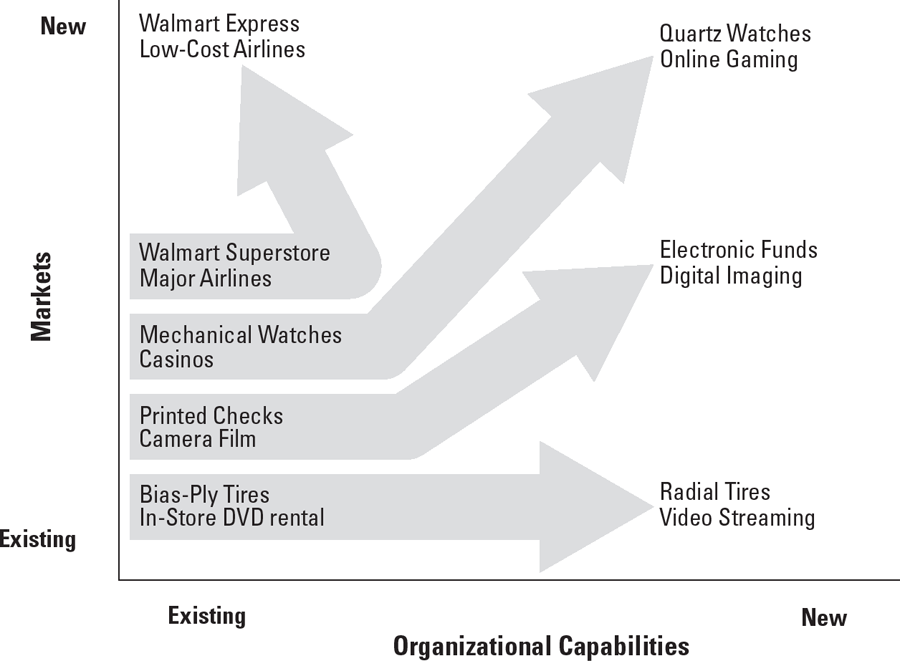

At a high level, the dynamics of success and failure can be described rather simply. Figure 1.1 illustrates this.

FIGURE 1.1 Innovation Streams

Think about the leadership challenges associated with competing in both mature and emerging technologies and markets. To simplify this, consider a space defined by innovations that are feasible and the types of customers served. Conceptually, innovation can occur in one of three distinct ways. First, and most common, is through incremental innovation in which products and services are made faster, cheaper, or better. Although these improvements may be difficult or expensive, they draw on an existing set of capabilities and proceed along a known trajectory. These advances build on the stock of organizational knowledge. The next generation of the automobile or cell phone, while technologically more sophisticated, is built on existing technology. When Boeing brings out the next airframe (e.g., the 787), the risks and expenses are huge, but the basic technology is largely an extension of previous capabilities.

A second way innovation can occur is through major or discontinuous changes in which improvements are made through a capability-destroying advance in technology.22 These innovations typically require a different knowledge base. For example, in the pharmaceutical industry, drug discovery was for many years based largely on ever more sophisticated uses of chemistry (small molecule development). With advances in biotech, the game has changed, and much drug discovery now is based on genetics and biology (large molecules), a different and potentially competence-destroying shift in the underlying capabilities needed by pharmaceutical companies. For Smith Corona, the development of computer-based word processing obviated the need for mechanical typewriters; for the Swiss in the 1970s, the advent of the electronic watch threatened the need for the precision mechanical engineering skills of mechanical watches. For the casino and newspaper businesses, the shift to online gaming and the digital distribution of content requires the development of an entirely new set of capabilities. In this sense, discontinuous innovations typically require capabilities or skills different from what the incumbent has, which often requires investments in new or unproven technology. Note that this does not mean that the technology is new to the world, only new to the company. When the quartz movement for watches emerged in the 1970s, the technology was well known to electronics firms but was discontinuous for the Swiss makers of mechanical watches.

Finally, innovation can also occur through seemingly minor improvements in which existing technologies or components are integrated to dramatically improve the performance of existing products or services.23 These so-called architectural innovations, while not based on significant technological advances, often disrupt existing offerings. These are largely what Christensen was referring to as “disruptive.”24 These typically begin by offering a cheaper alternative to a small segment of the original customer set and initially are not viewed as a threat to the incumbents because they appeal only to the low-end users where margins are already small. Over time, however, if the new innovation gets good enough fast enough, it can become useful to mainstream customers—in which case the entire pricing structure for an industry can collapse, as happened in the steel industry with the rise of mini-mills. For example, when mini-mills (large electric arc furnaces that used recycled scrap metal) emerged, they could produce only rebar, the crude reinforcing rods used in cement. But they could make this product 20 percent cheaper than large steelmakers could. For the steel producers, these were low-margin products, so they ceded this market to the newcomers. Over time, however, the mini-mill technology improved dramatically and allowed new companies like Nucor to produce higher-quality steel products at a much lower cost than the integrated producers. The result was waves of failure among the large steel companies.

Separate from the capabilities required for the innovation, firms can sell to existing customers or into new market segments. In the former case, previous customer insights help companies market their new products and services. They understand their customers and those customers’ preferences. They can also choose to enter new markets, with existing products and services or new ones. But here, because the customers are new to them, they may lack insight into these customers’ buying behavior. So, for example, in the early 1960s when Honda decided to import motorcycles to the United States, it was already the largest manufacturer of motorcycles in the world. But it had no insight into U.S. purchasers and initially failed to reach them. In the early 1970s, HP decided to produce digital watches. Although its leaders were technologically skilled, their lack of understanding about how to market consumer products ultimately doomed the venture. In contrast, when the Swiss began making low-priced electronic watches (the Swatch), they were able to position the new offering as a fashion statement that appealed to the low-end market. Separate from the capabilities needed for innovation are customer-based insights.

Now consider the evolutions we’ve just described through the lens provided by Figure 1.1. This is the most basic road map for leaders to determine their next moves to resolve the innovator’s dilemma.

Basically, exploitation is about getting better and better at doing business as usual. Over time, if firms are successful, they become more knowledgeable about their customers and more efficient at meeting their needs. Their strategy and the organizational alignment among capabilities, formal structures, and cultures evolve to reflect this. As we will see, the tighter the fit or organizational alignment, the more successful a firm is likely to be. However, in the face of increasing competition and decreasing margins, firms often seek to move into adjacent markets by addressing new customer segments or through discontinuous or architectural innovations that enable them to reap higher margins.

These shifts in strategy require a degree of prescience. Alas, incumbents often do not see the need to move from their origin—or do so late or incompetently.25 This is the story of Blockbuster, Smith Corona, Firestone, Kodak, Borders, and the other firms listed in Table 1.2. These companies failed at least in part because their leaders were unable to manage the transition from selling today’s products and services to existing customers to using new capabilities and products to sell to new customers. They were unable to be ambidextrous, unable to manage the innovation streams available to them. Ironically, it is almost always the case that these failed firms have the new technology to succeed, but their leaders fail to see the landscape that would enable them to capture value from it.26

Nevertheless, some leaders have been up the challenge of building parallel innovation streams and ambidextrous firms. Later in this book, we discuss how Shigetaka Komori at Fujifilm was able to leverage existing capabilities in surface chemistry to move from photographic film to a leader in coatings for electronic displays, or how Mike Lawrie at Misys and Ganesh Natarajan at Zensar were both able to build on existing capabilities and business models and explore new modes of delivering consulting and software services, respectively. We will also describe several leaders who were able to learn how to be ambidextrous when they had not been previously. We will discuss the personal and organizational renewal that Tom Curley underwent at USA Today. Curley was able to execute ambidextrous designs only after he and his colleagues learned the strategies that we are about to share. These leaders, and many others we describe in the following chapters, have helped us learn what it takes for organizations to be ambidextrous when confronted with disruptive changes in technologies, markets, and regulations. Often through trial and error, they have solved the innovator’s dilemma in ways that you can apply in your own organization. As you will see, this is, at heart, a leadership issue—and one that any thoughtful manager can learn.

Organization of the Book

The stories that we’ve shared in this chapter alone tell us that innovation is not a paint-by-numbers game. Over the past decade, we have studied and worked with a multitude of leaders and firms as they have wrestled with change. This book provides sound guidelines that can help leaders and their organizations avoid appearing on some academic’s list of formerly great firms that have failed. These suggestions reflect both research and the hard-learned lessons of leaders at successful companies like IBM and DaVita, as well as those at firms that did not make out so well.

Chapters 2 and 3 describe why ambidexterity can be so difficult for managers to achieve, and how successful firms can fall victim to their own success. We begin in Chapter 2 by showing how the demands of competing in a mature business (exploitation) require a different set of skills and organizational alignment from those needed to compete in new businesses and technologies (exploration). More challenging, we show how success at the exploitation game can actually undermine managers’ ability to explore; we call this the success syndrome. Yet if a business is to be ambidextrous and succeed in the face of change, it will need to do both. To make this challenge real, we show how Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon, has used exploitation and exploration to morph Amazon from an online bookseller into a powerhouse in web services. This example illustrates both the power of organizational alignment and its peril, revealing how leaders must prepare to adjust with changes in strategy.

Based on the concepts of exploitation and exploration, we return in Chapter 3 to the idea of innovation streams and show how long-term success typically requires organizations to evolve as markets and technologies change. We compare two old companies (both founded more than 130 years ago) and explore how one has been able to grow, while the other is in the process of failing after more than a century of success. This tale of two retailers begins with the rise and fall of an icon, the Sears Roebuck Company. Between its founding in 1886 and 1972, it became the country’s largest and most successful retailer. But as our story marches on, we see why, between 1973 and now, Sears has largely failed.

In contrast, Walmart, an arch rival of Sears, has grown through ambidexterity, rising from a small rural discount store to become a colossus of global retailing. Walmart sells in twenty-seven countries with more than 2 million employees and revenues of almost $500 billion. But Walmart is not the only member of the century club. We also consider the Ball Corporation, founded in 1880. Ball has evolved from a maker of wooden buckets to the dominant container company in the world—and a key player in satellites and space exploration. These rich histories illustrate in a microcosm the larger story that we aim to tell: how firms and their leaders can move their organizations from one success to the next while avoiding the success syndrome. We show that by thinking about change in terms of innovation streams, managers can use the ideas of organizational alignment developed in Chapter 2 to clarify how to organize in the face of disruptive shifts.

Part I thus provides a general framework for understanding ambidexterity. Part II (Chapters 4 and 5) illustrates in detail how leaders have wrestled with implementing this approach—some with success and some not. Although these cases often differ in the particulars, some important consistencies help us extract useful lessons for what it takes to implement an ambidextrous strategy and come out on top.

Chapter 4 describes how the leaders of six very different businesses were able to solve their own personal innovator’s dilemma. These examples illustrate how a newspaper (USA Today) was able to successfully meet the challenge of digital news, how a pharmaceutical company (CibaVision) was able to internally generate breakthrough products that increased its competitive advantage, how a division of HP was able to develop a new technology that had languished under its conventional organizational structure, how a large electronic manufacturer (Flextronics) has used ambidexterity to explore new business models through an internal start-up, how Cypress Semiconductor has developed a process to spur internal entrepreneurship, and how a kidney dialysis company (DaVita) has evolved to become a broader health care provider. Drawing on these successes, we identify three essential elements necessary for leaders to design ambidextrous organizations.

In Chapter 5 we expand on these insights and describe in detail a process that IBM used to generate organic growth, the Emerging Business Opportunity (EBO) process, which enabled it to increase revenues by more than $15 billion between 2000 and 2006. We also show how Cisco Systems attempted and failed at a similar effort. These extended examples model the lessons from Chapter 4 in a deep way. We then use the lessons from the successes and failures discussed in Part II to develop a framework that managers can use to help their own businesses become ambidextrous in Part III.

Chapter 6 identifies the structural conditions that are necessary for making ambidexterity real (what needs to be done). But these conditions, while necessary, are not sufficient. Ambidexterity is, at heart, a leadership challenge. In Chapters 7 and 8 we draw on the experiences of leaders who were successful at exploring and exploiting and show how ambidexterity can be implemented.

In Chapter 7 we describe how leaders from companies in advertising, software, health care, and the public sector have wrestled with the challenges of ambidexterity. Based on their successes and failures, we offer some guidance for the leadership skills needed to be successful with this approach to change.

In the final chapter, we tie together the lessons we have learned to provide a final framework for organizational transformation. We focus explicitly on the cultural and leadership challenges of managing across explore and exploit units, considering when ambidexterity can add value—and when it is not fit for the task. We illustrate these final points by describing from beginning to end how a CEO and his team were able to envision and implement an ambidextrous design and use it to drive new growth in a stagnant company.

Our experiences and the evidence we have reviewed here present a challenging picture for managers. Large, successful companies are failing at an alarming rate—and the rate of failure is increasing. The good news is that the rest of the book will provide an escape route for some and a source of inspiration for others. Most important, it offers a road map for winning through ambidexterity and potentially solving the innovator’s dilemma.

1. C. I. Stubbart and M. B. Knight, “The Case of the Disappearing Firms: Empirical Evidence and Implications,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 27 (2006): 79–100.

2. R. Agarwal and M. Gort, “The Evolution of Markets and Entry, Exit, and Survival of Firms,” Review of Economics and Statistics 78 (1996): 489–98.

3. R. Foster and S. Kaplan, Creative Destruction (New York: Currency, 2001).

4. Innosight, Executive Briefing (Winter 2012).

5. Stubbart and Knight, “The Case of the Disappearing Firms.”

6. “Netflix,” HBS Case 9-607-138 (Boston: Harvard Business Publishing, May 2007).

7. K. Frieswick, “The Turning Point,” CFO Magazine (April 2005): 48.

8. K. Auletta “Outside the Box,” New Yorker, February 3, 2014, 58.

9. “Equity on Demand: The Netflix Approach to Compensation,” Stanford GSB Case CG-19 (Stanford: Stanford Graduate School of Business, January 2010).

10. F. Salmon, “Why Netflix Is Producing Original Content,” Reuters, June 13, 2013.

11. D. Teece, G. Pisano, and A. Shuen, “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal 18 (1997): 516.

12. D. Sull, “The Dynamics of Standing Still: Firestone Tire and Rubber and the Radial Revolution,” Business History Review 73 (1999): 430–64.

13. E. Danneels, “Trying to Become a Different Type of Company: Dynamic Capability at Smith Corona,” Strategic Management Journal 32 (2011): 1–31.

14. M. Tripsas and G. Gavetti, “Capabilities, Cognition, and Inertia: Evidence from Digital Imaging,” Strategic Management Journal 21 (2000): 1147–61.

15. G. Colvin, “From the Most Admired to Just Acquired: How Rubbermaid Managed to Fail,” Fortune, November 23, 1998.

16. J. March, “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning,” Organization Science 2 (1991): 71–87.

17. Ibid.

18. J. G. March, “Understanding Organizational Adaptation” (paper presented at the Budapest University of Economics and Public Administration, April 2, 2003), 14.

19. C. M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997). See also C. M. Christensen and M. E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

20. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma.

21. J. Bowers and C. Christensen, “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave,” Harvard Business Review (January–February 1995), 43–53.

22. M. Tushman and P. Anderson, “Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments,” Administrative Science Quarterly 31(1986): 439–65.

23. R. Henderson and K. Clark, “Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms,” Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1990): 9–30.

24. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma.

25. Tripsas and Gavetti, “Capabilities, Cognition, and Inertia”; Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma; D. Sull, R. Tedlow, and R. Rosenbloom, “Managerial Commitments and Technological Change in the U.S. Tire Industry,” Industrial and Corporate Change 6 (1997): 461–500.

26. H. Chesbrough and R. Rosenbloom, “The Role of the Business Model in Capturing Value from Innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spin-Off Companies,” Industrial and Corporate Change 3 (2002): 529–55; Sull, “The Dynamics of Standing Still.”