Excerpt from the Introduction for Branding Humanity

Introduction

Violence Narratives and the Cultural Politics of Identity

Are you Bedouin? . . . “NO”

From Negro-land? . . . “NO”

I belong to you, a wanderer coming back

To sing with one tongue and pray with another

—Muhammad Abed-Alhai.1

IN MAY 2009, THREE YEARS AFTER the massive Save Darfur rally on the Washington Mall, I stood on Pennsylvania Avenue, right in front of the White House, to attend a demonstration with forty Sudanese activists and their Save Darfur allies. The activists were trying to regain visibility for the cause of the Darfurian people amid increasing American attention toward Sudan’s North-South conflict and efforts to fulfill the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the two sides (figure 1).2 One Darfurian activist I spoke with during the protest asserted that the Southern conflict and the approach of the January 2011 referendum on South Sudan’s independence were leading to compassion fatigue toward Darfur.

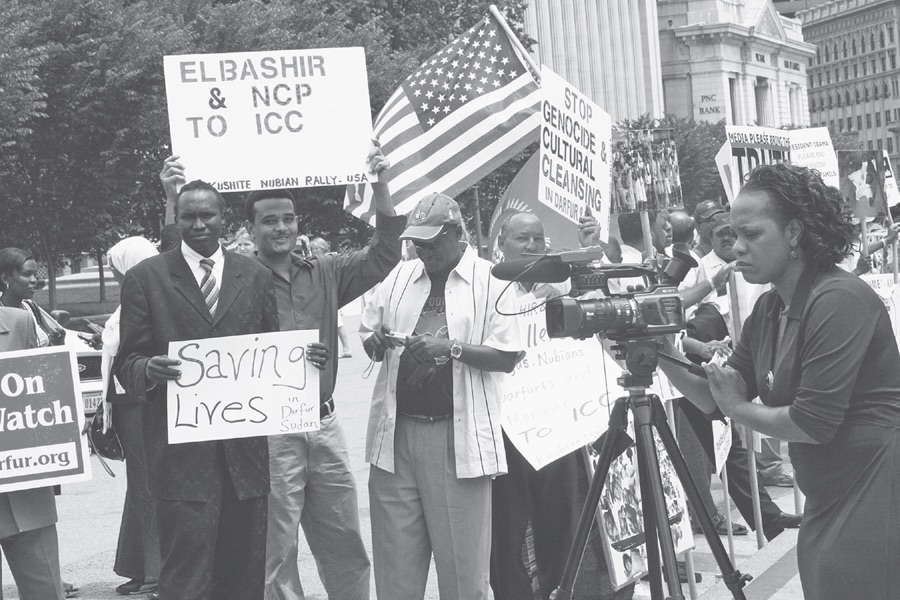

As I was waiting for the Darfur activists, who were at a nearby park rehearsing for the demonstration, I noticed a group of twelve Tamil activists holding posters of dismembered children and burned villages and schools and chanting, “Obama, Obama, you are Tamil’s only hope,” and “Send the media, send the NGOs, yes you can, yes you can.” I was taking photos of the Tamil protesters when the Save Darfur activists arrived. Unlike the Tamil activists, the Save Darfur protesters had their media coverage ready: The Voice of America and Aljazeera English Television were there to cover the event, as were photographers (figure 2). And, of course, I was there as well, as an anthropologist. I knew most of the Sudanese who were participating in the demonstration, and I had interviewed some of them as key figures in the Sudanese diaspora in the Washington, DC, area. The group included people who were originally from Darfur as well as people who identified themselves as Sudanese seculars or as political victims of the current regime.

The Save Darfur activists created a circle and placed themselves in front of the Tamil demonstrators. Their louder chants for justice in Darfur drew the attention of many passersby, especially that of touring high school students, who may have known more about Darfur than they knew about any other region in the world. I noticed that the Tamil activists stopped chanting and focused their attention on the Darfur group and their media team. My anthropological curiosity and interest in issues of transnational alliances, inclusion, and citizenship motivated me to shift my attention as well, from the Darfur group to the overshadowed Tamil protesters. I walked over to them and asked one if he had heard about the Darfur conflict, to which he responded that he hadn’t. Some of the Darfur activists I had interviewed noticed my movement toward the Tamil protest, and one of the Save Darfur group quickly approached the Tamil activists and invited them to join the Darfur circle. The two groups combined and began chanting against genocide in both places: “Obama, Obama, stop genocide in Darfur and Sri Lanka.” A member of the Darfur group who introduced himself to me as Zimbabwean chanted for peace, human rights, and justice for all humanity, calling for solidarity across the globe, while a Tamil activist interjected, “Media, media, bring the truth.” The media team noticed the merger and gave the Tamil activists a chance to speak about their cause.

A Tamil woman who thought I was a journalist thanked me for drawing attention to their protest. She said she had been in the United States for twenty-five years, and although she is American, she is still tied to her motherland through a community of Sri Lankans in the United States. She commented on the lack of media attention given to the atrocities committed against Tamil civilians by the Sri Lankan government during its crackdown on the Tamil Tigers in May 2009. Another activist noted the large community of Tamils in the Washington area, explaining that they had organized the protest in order to draw more news coverage and adding that they needed “to make a noise in order to draw media attention and to be heard by policy makers.” After the demonstration, some Darfurian and Tamil activists exchanged contact information, hoping to share experiences and to build solidarities.

I begin this introduction with the story of the Darfurian and Tamil alliance to highlight the uneven landscape of recognition and how that plays into the competition for transnational attention and visibility of activists’ causes of national exclusion. While the Darfur movement in the United States garnered ample media attention, other conflicts in Africa and elsewhere—as the Tamil example shows—had to compete for public notice. The relative success of the Darfur campaign can be attributed to a well-framed narrative of the Sudanese conflicts around gender-ethnic violence and genocide, inspired by the languages of human rights and humanitarianism and promoted at the height of America’s war on terror.3 The American-based Save Darfur campaign itself endorsed this narrative and helped to circulate it by mobilizing faith-based organizations, incorporating some Sudanese activists, and engaging the media and policy makers in order to increase the conflict’s visibility. At its inception in 2004, the campaign was focused primarily on the crisis in Darfur, and it soon came under criticism for its approach to media advocacy and its simplistic gendered and ethnic categorization of violence.4 The polar categories of Muslim/Arabs versus Christian/black Africans dominated the political campaigns for Southern Sudan in the United States, and the Save Darfur campaign relied on similar categories of gender and ethnic violence committed by Muslim Arabs against Muslim black Africans. Not all Darfurians in Washington were content with the Save Darfur coalition and its strategies. Some told me that many Darfurians did not join Save Darfur because they felt that they were recruited as informants and not agents capable of speaking for themselves and the plight of their people. They also complained that the campaign simplified complex political debates about diversity, inclusion, and citizenship rights in the Sudan.

The alliances and solidarities that many Sudanese social actors and activists create with other Americans, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and policy makers in Washington, DC—including their responses to the Save Darfur efforts—provide insight into how members of the Sudanese community in the Washington metropolitan area engage in Sudanese cultural politics from afar. Many of them utilize these connections and social networks to respond to the dynamically shifting ethnic divisions and conflicts in their homeland, and the subsequent political constructions of their cultural identities, as exiled Sudanese nationals, Muslims, non-Muslims, and as American citizens and noncitizens. In the years following September 11, 2001, immigrant communities in the United States have experienced the impact of political tensions and racial panics in various ways.5 The experience of the Sudanese community, however, has been uniquely complex because the life histories of Sudanese immigrants are shaped by ethnic divisions and the realities of war and conflict at home and by the representation of these realities in political campaigns, Western mainstream media, and other such forums. Northern Sudanese, who are mostly Muslim and Arabic-speaking, bore more of the brunt of the “war on terror” and its aftermath of labeling and exclusion than did Southern Sudanese refugees and immigrants, who are mostly Christian and hail from different ethnic backgrounds. Similarly, the escalation of the Darfur conflict in 2003 and the political campaigns that defined the conflict as one of genocide and ethnic cleansing have distanced Darfurians from a Northern-Muslim Sudanese identity in exile. Although many Sudanese exiles in the United States migrated to escape the violence of war, ethnic conflicts, and structural inequities, ethnic divisions continue to be mobilized and reproduced in new forms in American official discourses and mainstream media reportage about Sudan and its violence. The Western insistence on a narrative that emphasizes ethnic division engenders new articulations of identities and new claims of national and transnational belonging, alliances, and affiliations.

Figures

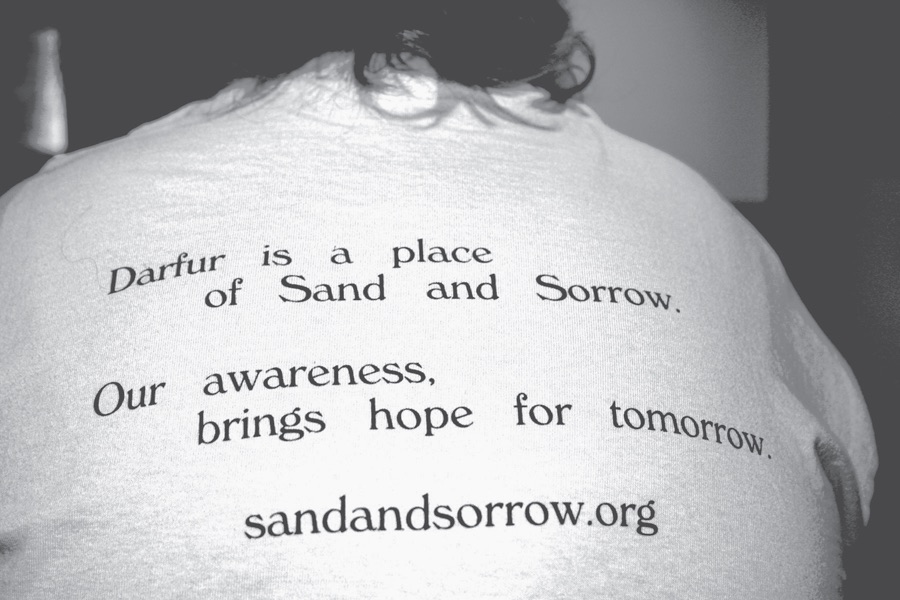

Figure 1 Student wearing a T-shirt inspired by George Clooneyâs documentary Sand and Sorrow. STAND conference, Washington, DC, 2009. Photo by author.

Figure 1 Student wearing a T-shirt inspired by George Clooneyâs documentary Sand and Sorrow. STAND conference, Washington, DC, 2009. Photo by author.  Figure 2 Darfur protest in front of the White House, Washington, DC, 2009. Photo by author.

Figure 2 Darfur protest in front of the White House, Washington, DC, 2009. Photo by author. Notes

1. Muhammad Abed-Alhai is a renowned Sudanese poet whose work is known for its focus on questions of modernity and identity. He argued for the modernization of Arabic poetry and discussed the influence of British and American poetry on his own writing. Regarded as one of the “Forest and Desert School” pioneers in the Sudan, Abed-Alhai had many publications, including his five-poem collection, “ala‘awda ila Sinnar” [Back to Sinnar.] He died in Khartoum in August 1989, at the age of forty-five. The epigraph from “Back to Sinnar” is my translation. See http://www.tawtheegonline.com/vb/showthread.php?t=5863 for documentation of Back to Sinnar, accessed May 15, 2018.

2. Comprehensive Peace Agreement, accessed February 1, 2013, http://www.sd.undp.org/doc/CPA.pdf.

3. Bob, Marketing of Rebellion.

4. The Save Darfur Campaign was later transformed from a campaign focused primarily on Darfur to a broader campaign focusing on genocide globally in 2010.

5. Mamdani, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim; Shryock, Islamophobia/Islamophilia.